Labor Day 2015: Will new overtime rules be game changer for progressive political campaigns?

Guest commentary by Judy Stadtman

If the new overtime regulations proposed by President Obama go into effect, I will get a raise. Not just a measly little pay bump, either; I will receive a salary increase that is roughly triple the average annual increase guaranteed under my union contract.

In fact, many highly-skilled professionals with extensive experience in progressive campaigns and policy advocacy will likely go home with fatter paychecks if the new rules take effect in 2016. But rank-and-file campaign workers at the low end of the pay scale — who may be expected to work 60-70 hours a week for as little as $2,000 a month — stand to gain the most from the modernization of overtime rules.

A dirty little secret

The unwholesome little secret of progressive organizations and political candidates is that the exploitation of workers is excused as an inevitable factor of winning campaigns.

Just as with big corporations that put profits before people, cash-strapped candidates and campaigns stretch their budgets by minimizing overhead costs. That translates into keeping staff salaries low and work hours high, plus convincing as many people as possible to do the work for free.

Entry-level campaign organizers, who have virtually no discretion over when, where and how to complete work assignments and no control over their work hours, are responsible for recruiting, training and managing the unpaid volunteers who are also essential to executing today’s high-intensity model of campaign operations.

By the numbers

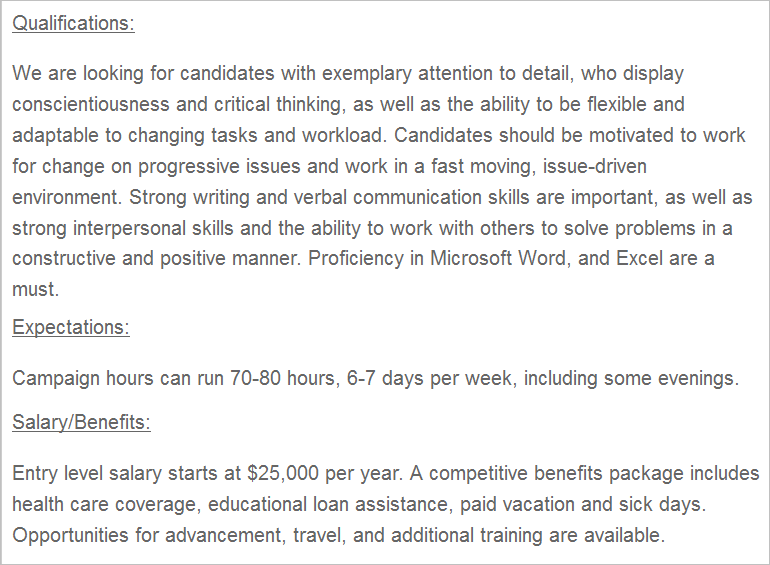

To qualify as overtime-exempt “professionals” under current regulations, full-time entry-level campaign workers can be paid salaries as low as $24,000 a year – the equivalent of $11.54 an hour.

For a staffer who is expected to work 10-12 hours a day, 6 to 7 days a week for the duration of a campaign, a $24,000 salary converts to average hourly earnings of roughly $7.10 an hour — less than the federal minimum wage.

According to wage data analyzed by glassdoor.com, average compensation for deputy field organizers is $34,000 a year, or about $16.35 an hour based on a 40 hour work-week – not a princely sum for an employee who is expected to work executive hours, with no days off and little or no power to control his or her own workflow.

A field organizer earning $3,000 a month and working a typical campaign schedule of 65-70 hours a week would ultimately take home the equivalent of roughly $10.50 an hour. As it stands, all of these practices are mostly legal.

Hard choices

If the salary threshold for overtime-exempt employees rises from the current minimum of $23,660 to the proposed minimum of $50,440, the progressive political industry will be faced with an assortment of hard choices: substantially raise the pay of bottom-rung campaign staff; fork over formidable sums of overtime pay; adapt to a 40-hour work-week; recalibrate campaign operations to rely on fewer paid staff; or, dramatically cut spending on other essential campaign activities, such as paid advertising and direct mail.

Since none of these options is particularly compatible with the fast-paced, anxiety-ridden reality of 21st century campaign culture, some operations may be looking for a work-around. That “work-around” is likely to involve the misclassification of regular, full-time organizing staff as independent contractors.

Less than ethical organizations and campaigns already use this tactic to hold down staffing costs. In this scenario, a campaign worker is paid a fixed wage (sometimes as low as $2,000 a month) to deliver organizing services under the direction of a centralized campaign manager or field director.

This could be a fair labor practice, except when the field director schedules an organizer’s daily workload, dictates when, where and how assignments are to be completed, imposes intensive and inflexible reporting requirements, or specifies the number of hours the organizer is required to spend on campaign activities each day — which once again, can be 10-12 hours a day, 6 to 7 days a week.

Under federal law, any one of these management interventions would automatically disqualify a campaign worker from being paid as an independent contractor.

The feel good factor doesn’t pay the rent

Personally, I hope the prospect of new and improved overtime rules will provoke a round of soul-searching among progressive advocacy organizations and major donors about how we do our work and the quality of the jobs we create in the process of advancing our goals.

It is noteworthy that the proposed overtime change coincides with mounting evidence that the most effective campaign tactics involve unscripted, personal interactions with voters — which is precisely the quality and intensity of contact that rank-and-file political organizers generate through direct outreach and volunteer engagement.

The intrinsic benefits of serving the common good are significant and undeniable. But the feel good factor doesn’t pay the rent. The entry-level work of organizing for change requires creativity, flexibility, self-regulation and above-average technical, communication, and social skills. It should be rewarded at least as generously as the $15.00 per hour now demanded by fast-food and retail workers across the country.

Regardless of the altruistic orientation or future political ambitions of the people hired to get the work done, campaign jobs are just like any other job that paid workers perform to meet the productivity standards of their managers and bosses.

If we truly believe that workers at Walmart and McDonald’s deserve better wages and working conditions, there is no legitimate excuse to reward the hard work and passionate commitment of political campaign workers with low pay, no days off and excessive uncompensated overtime.

Walking the talk

Lifelong liberal activists may find it difficult to acknowledge that less than exemplary labor practices exist in the progressive movement. Even those who have worked as paid campaign staff may be tempted to tolerate worker mistreatment as part of the necessary sacrifice we make to win change.

Certainly, not all progressive organizations and campaigns are guilty of low-road employment schemes; in New Hampshire, most advocacy campaigns and political groups compensate political staff and paid canvassers fairly. But the problem won’t go away unless we insist on the fair and humane use of human resources in high-performance political campaigns.

Progressive activists are constantly encouraged to live our values and “walk the talk” (phrases that, unfortunately, are most often used to persuade volunteers and donors to give more time or money to a candidate or cause).

As we address the urgent need to update federal overtime rules and the potential impact it will have on the political industry, let’s not forget that “walking the talk” means honoring the fundamental progressive principle of valuing work, and demanding fair treatment for all workers no matter what kind of job they do.

Judy Stadtman is a legislative reform and political campaign specialist. She currently holds a senior staff position with a New Hampshire labor organization. The opinions expressed in this commentary are her own.