Education, more than income, predicted who in New Hampshire would vote for Donald Trump

In a detailed analysis of national voting data, Nate Silver concludes that educational attainment is the critical factor in predicting partisan voting shifts from 2012 to 2016.

Silver, the founder of FiveThirtyEight, compiled a list of the 981 U.S. counties with a population of at least 50,000 people and ranked them by share of the population with a four-year college degree.

He found Hillary Clinton improved on President Obama’s 2012 performance in 48 of the country’s 50 most-well-educated counties, besting Obama’s margins by almost 9 percentage points. At the same time, Silver determined that lower-income counties were no more likely to shift to Trump once you control for education levels.

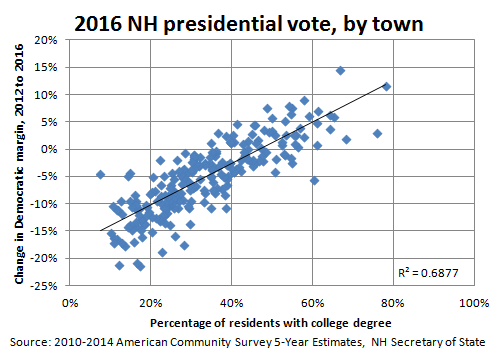

Using a similar approach, we studied the New Hampshire town-level results and reached a similar conclusion. We compiled state voting results from the Secretary of State’s office and compared Obama’s share of the two-party vote in 2012 with Clinton’s for each town.

We analyzed the results based on each town’s share of those 25 and older with a four-year degree and by the median household income using data from the U.S. Census Bureau 2010-2014 American Community Survey.

As with Silver’s study of national results, we found a stronger correlation between educational attainment and the four-year shift in partisan voting (a correlation coefficient of 0.69 for you data geeks) than for income (a correlation coefficient of 0.44).

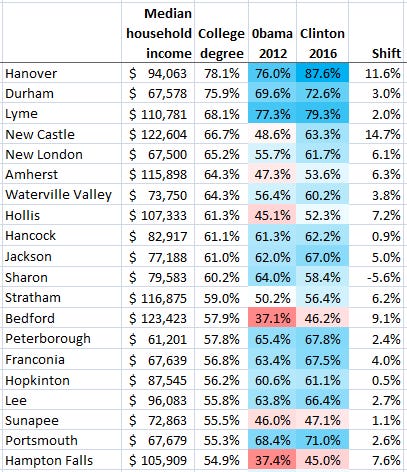

We took a look at the 20 New Hampshire towns with the highest levels of educational attainment by ranking the towns by the share of the population with a four-year college degree.

Other than the high level of educational attainment, the communities are a fairly varied group. The list includes college towns (Hanover and Durham), wealthy Republican enclaves (Bedford and Hampton Falls) and economically diverse Democratic-leaning towns (Peterborough and Franconia).

In 19 of the 20 towns with the highest level of educational attainment, Clinton received a larger share of the two-party vote than Obama did four years ago. She outperformed the president in these towns by an average of 4.6 percentage points – even though statewide, she underperformed Obama’s 2012 vote tally by over five percentage points.

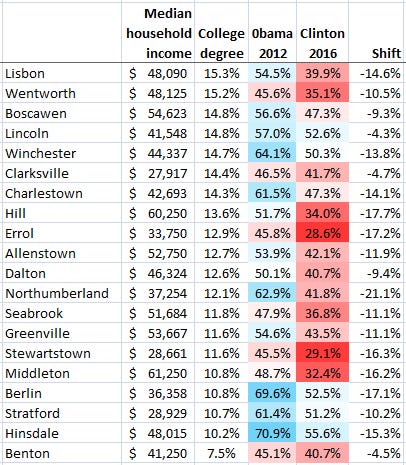

A look at the 20 New Hampshire towns where the smallest share of the residents has four-year degrees is even more striking. This list includes both Democratic- and Republican-leaning towns. It has some of the state’s most economically disadvantaged towns as well as some with median household incomes near the state’s average. Clinton underperformed Obama in all 20 towns – by an average of 12.5 percentage points.

Silver cautions that his analysis is just a starting point for further research. “Nonetheless,” he wrote, “the education gap is carving up the American electorate and toppling political coalitions that had been in place for many years.”

The electoral implications of the education gap and the failure by policy makers to address the growing economic disparity were predicted by left-leaning philosopher Richard Rorty in 1998. “Something will crack,” he wrote:

“The nonsuburban electorate will decide that the system has failed and start looking around for a strongman to vote for — someone willing to assure them that, once he is elected, the smug bureaucrats, tricky lawyers, overpaid bond salesmen, and postmodernist professors will no longer be calling the shots. … All the resentment which badly educated Americans feel about having their manners dictated to them by college graduates will find an outlet.”